Pitons are reliable, but they damage rocks.

©Glen Denny

Compared to other major sports such as mountain climbing and skiing, climbing has a smaller population. This is because it is difficult to handle equipment, requires specialized knowledge, and requires physical strength. The risk of injury is also high.

On the other hand, many people are in love with the culture of climbing. Patagonia is admired not only for its founder Yvon's approach to the environment, but also because he was an extreme person and a serious climber at heart.

Yvon sells his gear in Yosemite National Park. ©Tom Frost

In 1953, at the age of 14, Yvon began climbing and fell in love with the sport, and in 1966 he founded Chouinard Equipment, a brand that would become the predecessor to Patagonia. There, he improved on the soft-iron pitons that had been the mainstream in Europe until then, and developed an original piton that matched the quality of American rock and could also be retrieved. This product was well received, and by 1970, the company had grown to become the largest manufacturer of climbing gear in the United States. However, although the pitons were first-rate, the pitons themselves could cause serious damage to the rock.

Those were the days when one would use any means necessary to reach the summit. It was commonplace to use hammers and chisels to chip away at rocks in order to advance, or to embed artifacts in rocks. So even pitons were accepted by many people. One day, however, Yvon saw a rock face that had been torn apart by pitons, and he called for the pitons to be stopped. From there, the concept of "clean climbing" was born, in which climbers climb the rock as it is and return it as it is.

Yvon with hanging gear for climbing rocks, taken in 1972. ©︎Tom Frost

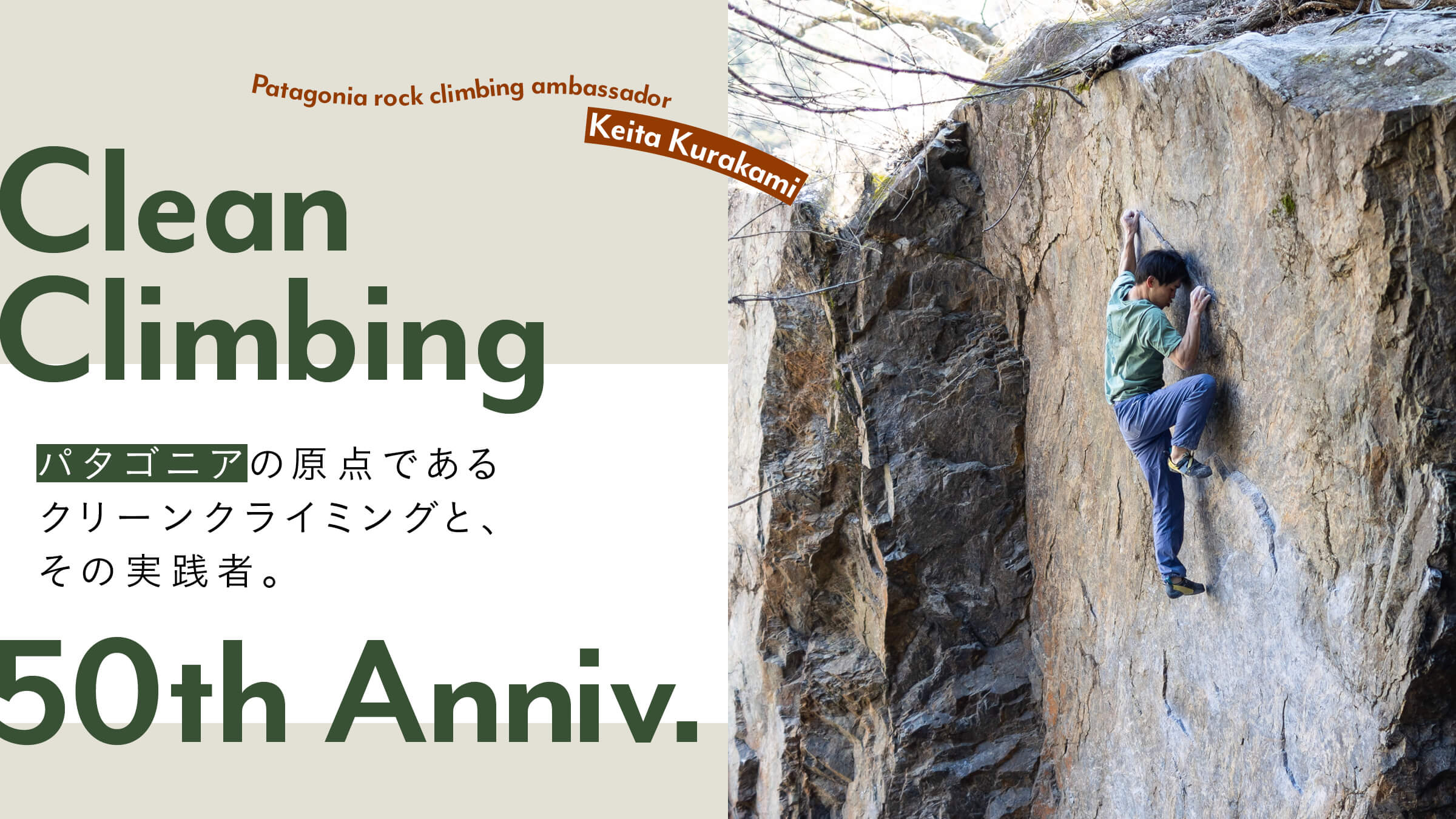

This year marks 50 years since we began advocating this idea. In order to keep this thought alive and to pass it on to the next generation, a capsule collection of clean climbing items will be released. We will talk about the items later, but for now, let's learn about climbing and clean climbing through the story of Keita Kurakami, a rock climber who is the pride of Japan.

Climbing huge rocks and walls in a simple style.

PROFILE

Born in Gunma Prefecture in 1985. He is a rock climbing ambassador for Patagonia. He pursues a simple style of climbing and tries to express freedom and diversity. He has climbed many difficult routes and has named many routes after himself both in Japan and abroad. While working as a professional climber, he also trains to play the shakuhachi, a traditional Japanese musical instrument.

Instagram: @keitakurakami

As he showed us the shocking footage, he said, "I've fallen many times. As soon as I know I'm going to fall, I give up and get into a landing position," said Kurakami, a rock climbing ambassador for Patagonia. He is a professional rock climber who climbed his first rock when he was in high school and has been climbing for nearly 20 years.

As Mr. Kurakami says, "Many people probably mix up bouldering and climbing," and indeed, the differences between rock climbing and bouldering are vague. Let's start there.

The word "climbing" is derived from the English word "climb. It means "to climb. So, to put it simply, climbing is climbing, climbing rocks is climbing, and climbing trees is climbing. Rock climbing is rock climbing, and within the field of rock climbing is the category of bouldering.

The word "bouldering" is derived from the English word boulder. The meaning of the word is "boulder. Therefore, bouldering means climbing boulders of about 4 to 5 meters. Anything higher than that is in the genre called high bouldering (it is more subdivided, but search for more details).

One day in March, Mr. Kurakami and I headed for Ontake Boulder, the Mecca of bouldering in the Kanto region.

After walking along the river for about 20 minutes, you will find Hikageishi, the symbolic rock of Ontake Boulder. It is about 7 meters high. This is the rock Mr. Kurakami climbed on that day. Why do you climb the rock in the first place?

I like to climb where no one has climbed before. That is called "pioneering." No one knows how to climb it, and no one knows if it is possible or not. But I try, thinking that I might be able to climb it. Even if you don't make it to the summit, the experience will remain with you. That process is a very good time for me.

When you are actually up close and personal with a boulder, just looking up at the rock from below, you never know where your fingers will be and where your feet will be. If someone has already climbed the rock, the chalk (non-slip) will be a landmark, but this is not the case with unclimbed lines. You may reach for a spot where you think there is a snag, only to find that there is nothing there.

To be honest, I am afraid (laughs). (Laughs.) There are times when I actually get halfway up and think, 'This is a bad idea. Sometimes you can't get caught anywhere, or on the other hand, there is no way to get down, so you have no choice but to climb up. It is difficult to judge, but I enjoy the process of overcoming that fear by training myself physically and mentally.

On this day, Mr. Kurakami did not have a mat under him or a lifeline of any kind. With no assurance of safety, he climbed at a speed that made even those of us watching him nervous.

Patagonia's approach to clean climbing is to accept nature as it is, climb as we are, and give it back to nature in its original state. Normally, I would lay out a mat or not, depending on the environment and the subject of the climb, but this time I climbed without a mat because I wanted to show you a simple form of climbing. So you don't use any artificial materials other than non-slip chalk and shoes. So you have to take more risks when climbing, and you have to have an eye for detail in the rock.

On the other hand, looking back at the history of climbing, there is a past of forced human modification on various rock walls and mountains.

There is a famous story about a route in Patagonia, South America, which is also the Patagonia logo. It's called the Compressor Route. A long time ago, a climber carried a compressor all the way up to the rock face of the mountain to make his first ascent, and he hit a bunch of bolts. It's a terrible story, but in 2012, a Patagonia climber made the climb without using those bolts and then removed most of the bolts on the line. That was sensational.

After the climb, chalk on the rock wall is cleaned thoroughly.

Japan is no exception, and one can see leftover equipment in many places.

However, when you are climbing a huge wall, you need to intervene with tools. We need harnesses, we need ropes, we need carabiners, and so on. But we must not harm nature.

From left to right: nuts, coming device (a.k.a. cam), and pitons.

All of these are used to insert into cracks in the rock and hook a rope as a lifeline. The pitons shown on the far right were made by the aforementioned Chouinard Equipment, which are hammered into the rock so forcefully that they cause considerable damage to the rock. In this respect, the nuts and cams do not damage the rock.

I screw them into the cracks like this. "I start from a place where there is a large space, and then I put it in a place where it will be caught, so I give it a firm grip there. Then, even if you put all your weight on it, it won't fall out. Sometimes it does fall out, though (laughs)."

It is also easy to remove, just move it to the side where there is more space. It has become an indispensable tool for today's climbers.

Climbing is a way to learn to live flexibly. You can resist the situation, or you can accept it, or you can give up on it. When you are in the overwhelming presence of nature, you are required to do so at every moment, and I am learning how to behave in such a situation. And clean climbing is the way of thinking and the way to sharpen that sense the most.

I don't know if "daredevil" is the right word, but I do know that rock climbers are always next to danger. People who live in such an environment on a daily basis are unfazed, gentle, and full of creativity. You are no exception, and neither is Patagonia. Climbing is cool.

Mr. Kurakami's hands are scarred from his many battles.

A special collection celebrating 50 years of clean climbing.

Yvon Chouinard, a former member of the American Society for the Advancement of Science, said, "Clean climbing means facing our ego and curbing it, facing nature and humbling ourselves to it, striving to overcome our self rather than to conquer the world. These ideas stir us and are the excitement we need as we face the great challenge of saving the planet."(Yvon Chouinard)

A capsule collection reminiscent of the climbing styles of the time went on sale on Thursday, March 17. Finally, we introduce a part of the collection.

M's Cotton in Conversion MW Rugby Shirt ¥13,750 This classic rugby shirt can be worn casually as everyday wear. Climbers in the past used this durable fabric to their advantage and actually wore it while climbing.

M's Clean Climb Catalog Regenerative Organic Certified Cotton T-Shirt ¥5,280 This T-shirt is printed with the cover of the Chouinard Equipment catalog published in 1972. The material is, of course, organic cotton.

M's RPS Rock Pants ¥15,400 It has excellent stretch and is fully equipped with protection against rocks and friction. It has a durable water-repellent coating that is perfluorinated compound-free, reducing environmental impact.

Clean Climb Patch: Dirt Bag Stone Blue ¥5,500 This quick-drying nylon cap is made from recycled fishing nets. This item is also highly breathable, making it a more functional version of Patagonia's classic McClure hat.